Chennault and the Wuhan Firebombing

- By Peter Harmsen

- 3 October, 2015

- 1 Comment

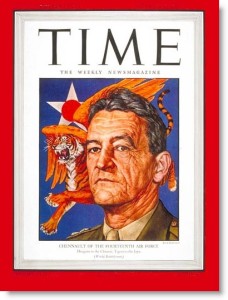

US Major General Claire Lee Chennault, the founder of the famed Flying Tigers, played a major role in the planning and execution of the firebombing of the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 1944. This was in his capacity of commander of the Fourteenth Air Force, based in southwest China. Faced with a sweeping Japanese offensive down the provinces of eastern and central China, he had been pushing since June 1944 for a bombing raid on Wuhan, the main Japanese staging area, according to his memoirs, Way of a Fighter, published in 1949.

Chennault described difficulties getting the necessary backing for his proposal, blaming Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, the senior US commander in the China theatre, for lack of enthusiasm. Only after Stilwell was pulled out of China did Chennault get the support he needed from Stilwell’s replacement, Lieutenant General Albert Wedemeyer.

Chennault was given responsibility for the overall planning for the mission, which was to target Wuhan’s main warehouse district along the river front. He wanted the B-29 Superfortresses, which were to carry out the bombing, to drop only incendiaries. Curtis LeMay, the commander of the B-29s in Asia, preferred to use high-explosives. The result was a compromise in which four in five Superfortresses carried incendiary bombs.

The stage was now set for the bombing, which took place on December 18, 1944. In his memoirs, Chennault was remarkably honest about everything that went wrong. The 77 Superfortresses, supported by 200 planes from the Fourteenth Air Force, attacked in seven waves, 10 minutes apart. The first waves, according to Chennault, left a thick blanket of smoke over Wuhan. As a result, when the last waves arrived, visibility was zero, and few of the aircraft were able to drop their bombs even within the city limits.

Still, the accompanying planes from the Fourteenth Air Force scored considerable hits, as they targeted surrounding airfields as well as Japanese planes that had been scrambled to intercept the B-29s or were simply attempting to flee the inferno in Wuhan. At the end of the day, the Fourteenth Air Force claimed to have destroyed 64 Japanese aircraft while not losing a single plane itself.

On the ground too, the mission had a huge impact, Chennault explained, while only hinting at the collateral damage: “Fires burned for three days, gutting the docks, warehouse areas, and large sections of the foreign quarters.” Strategically, it had the effect of taking out the material base of the Japanese offensive in east China. “Starvation,” he wrote, “crept down through East China from the blackened ruins of the Hankow (1) warehouses like a slow paralysis, marking the beginning of the end for the Japanese armies in the corridor,” Chennault wrote.

According to Chennault, the Wuhan attack impressed LeMay, and when the B-29 commander moved to the Pacific shortly afterwards to direct the bombing offensive of Japan’s home islands from there, he was a convert. This was the origin of the firebombing of Japan’s cities that “burned the guts” out of the country and forced it to its knees, even before the nuclear bombs of August 1945, at least as described by Chennault in his memoirs.

(1) Also spelled Hankou. One of the original three cities that had long ago merged into the tricity of Wuhan.

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

Fine article on an operation that has received too little attention.