The Mysterious Case of E.A.R. Fowles I

- By Guest blogger

- 6 February, 2015

- 1 Comment

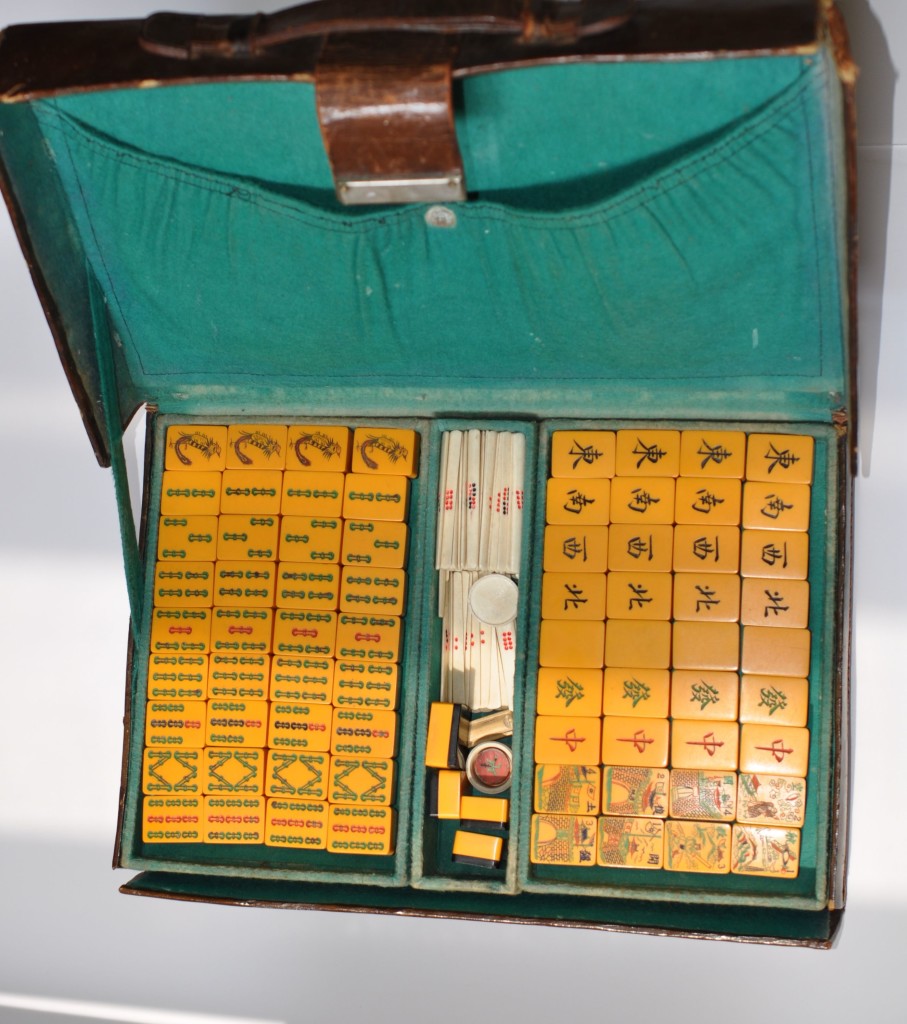

This is the first installment in a two-part series about a wartime riddle involving a unique mahjong set full of anti-Japanese symbolism. It belonged to an elusive E. A. R. Fowles and was transported on board a ship that ended up on the bottom of the ocean. Read on in this fascinating investigative piece by Woody Swain, first carried on the deeply interesting and richly illustrated website Mahjong Treasures.

In his semi-autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun, G. J. Ballard describes what befell British citizenry in Shanghai, China during the Japanese Occupation of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). It depicts events immediately following December 7, 1941, when Imperial Japan, having attacked Pearl Harbor, took over and occupied the long-established American and British settlements of the city. British and American civilians were rounded up by Japanese soldiers, and many were marched to their deaths in brutal Japanese internment camps. Ballard was lucky; his parents survived the death squads and he was reunited with them after the war. Others weren’t so fortunate.

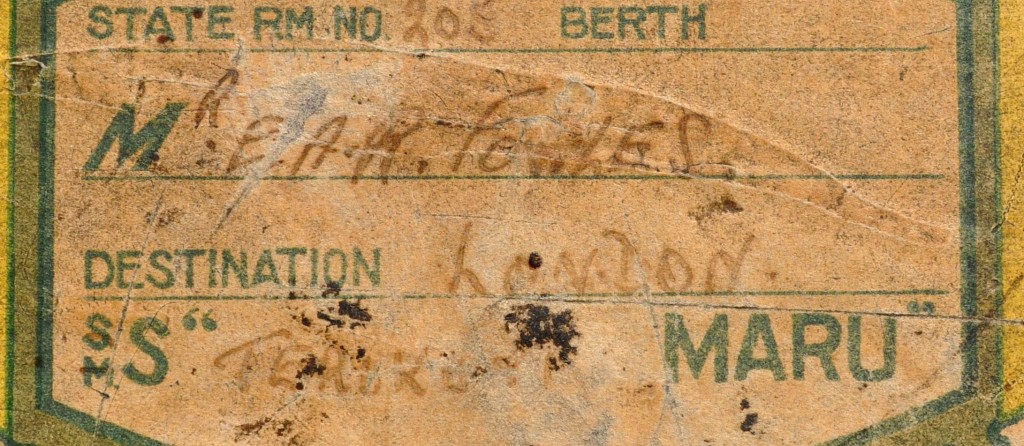

A small leather beat-up Mah Jong case tells another tale about another family who might have escaped the horrible chaos of 1941 Shanghai. Sometime before the Autumn of 1939, a certain Mr. E A. R. Fowles, for reasons currently unknown to us, booked first-class Stateroom No. 205 on the Japanese N.Y.K. liner M.S.Terukuni Maru scheduled from Shanghai to London. We know all this because his name is on the luggage sticker affixed to the Mah Jong case.

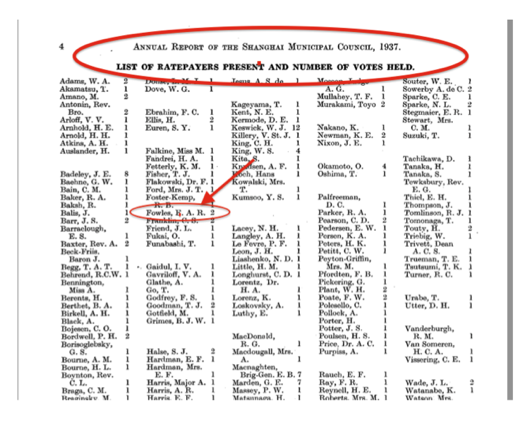

What is missing on the sticker is a date of embarkation. Also unknown is who he traveled with. Moreover, until I can find a deck plan of this liner, I don’t know if this was a suite or a single room. We are not exactly sure who this man was, but according to immigration records, there was a Mr. E.A.R. Fowles residing in Shanghai who went there with his wife and three children in 1925 on the P&O Liner Morea. We don’t know Fowles’ occupation, but most likely he worked in the British finance world along the Bund in Shanghai and lived quite elegantly with Chinese servants in the British Settlement District. Here’s what else we know about our Mr. Fowles; he was a prominent “rate-paying” resident on Shanghai’s Municipal Council, present at its Annual meeting on April 14, 1937 and accorded “two votes” out of a total of 251.

At any rate, the total number of that august Shanghai Council, with a list composed mostly Anglican surnames, numbered just 334. Since there were 60,000 business people—not including Chinese— living in Shanghai since the early 1930’s, the Fowles family was on quite an exclusive list. E.A.R. Fowles’s name doesn’t appear anywhere again on the 468 page report.

Fowles, along with the Council was charged with maintaining a standard of living for the Brits in the long-established “International Sector” extant since the 1800’s— from The Library and Orchestra Committees, to the drinking water, medical services and the police force. It also charged its ex-pat community to coexist with the Chinese, their Chinese servants and the increasingly hostile Japanese military. The 1937 minutes for The Council state what must have become a fast developing ad-hoc mission:

” The duty of the Council during these abnormal times is to adopt every means in its power to ensure the safety of life and property within the area under its control, and to preserve the peace, order and good government of the International Settlement…All persons are urged,… to bear cheerfully any inconvenience to which they may be subjected and to assist generally in preserving calm, peace and good order.”

Looking back, their society was a powder keg about to be lit. Indeed, the “Emergency Branch” report of the Council continues:

[The Ambulance Service] was constantly in demand and handled no less than 901 casualties suffering from bomb, shell, shrapnel…from hundreds of injured at the aerial bombing at the Bund and Nanking Road,…and the striking, by an unidentified projectile,…on August 23 [1937], at which calls the casualties were so numerous and the conditions so appalling that no record of the number of patients actually conveyed in ambulances …could be kept.

Perhaps it was a family emergency abroad, or perhaps Fowles sensed the forthcoming onslaught. We don’t know if he even picked up the ship in Shanghai. Whatever happened, his proper British world was unraveling, and people were fleeing Shanghai — just as many were fleeing Nazi Germany. He must have decided it was now the time to leave. (Ironically many Jewish people fled east by ship to Shanghai during this period, and the story of the Shanghai Ghetto is a miraculous one. The Japanese, as cruel as they were during those years, were not anti-Semitic. While there were indeed wartime hardships in Shanghai for Jewish people, the Japanese would not tolerate their persecution).

At any rate, Fowles’s itinerary from China to England called for a fortnight transit across the Indian Ocean into the Suez, the Mediterranean, and up into the Thames to London with numerous ports in between. How could Japanese ships be allowed to sail into European waters in the late 1930’s when England was at war with Germany? From 1937 until 1940, Japan was still regarded as a “neutral” country by England. Basically even though Imperial Japan’s atrocities in Mainland China— in their quest for oil and resources—resulted in such appalling massacres as in Nanking and Manchuria, diplomatic relations between the countries held and trade continued.

(To be continued)

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

[…] Via Peter Harmsen’s WW2 In China blog I found a link to this post from Mahjong Treasures. […]