This is the first instalment in a two-part series about Shanghai’s dark legacy– buildings that housed brothels used by the Japanese Army during World War Two. This article, written by Sue Anne Tay, first appeared on her website shanghaistreetstories.com, a great resource for those who want to explore the rich history of China’s most cosmopolitan city. Also check out their Facebook page.

This is the first instalment in a two-part series about Shanghai’s dark legacy– buildings that housed brothels used by the Japanese Army during World War Two. This article, written by Sue Anne Tay, first appeared on her website shanghaistreetstories.com, a great resource for those who want to explore the rich history of China’s most cosmopolitan city. Also check out their Facebook page.

If you look closely, the legacy of Japanese presence in pre-war and war-time Shanghai can be found across the city’s old neighborhoods, dating back to their emergence as a major power after prevailing in the first Sino-Japanese war in 1895, right up to the military occupation that ended in 1945. I’m not talking about patriotic memorials or museums but evidence of past Japanese lives in old neighborhoods, especially in Hongkou district located north of Shanghai where the Japanese expatriate community flourished in the early 20th century.

Along Shanyin Lu (山阴路) in north Hongkou, one alley that originally housed Japanese families had characteristically squat house entrances with sliding wooden screens. In the now-demolished homes around Gongping Lu (公平路), I spied old kanji letterings on doors and Japanese flower motifs carved into beams. Local residents led me up to a fortified roof of an old four-storey building where keyholes were built into raised walls for Japanese canons and snipers. During the war, soldiers would have been able to see black plumes of smoke in the distance where heavy fighting took place along Suzhou Creek.

Along Shanyin Lu (山阴路) in north Hongkou, one alley that originally housed Japanese families had characteristically squat house entrances with sliding wooden screens. In the now-demolished homes around Gongping Lu (公平路), I spied old kanji letterings on doors and Japanese flower motifs carved into beams. Local residents led me up to a fortified roof of an old four-storey building where keyholes were built into raised walls for Japanese canons and snipers. During the war, soldiers would have been able to see black plumes of smoke in the distance where heavy fighting took place along Suzhou Creek.

But nothing is more haunting than the legacy of comfort houses (慰安所) that were created by the Japanese Imperial army for abducted Chinese (along with Korean, Indo-Pacific) women to cook, clean and perform sexual services for their soldiers. As the Japanese military advanced across China during the war, an estimated 200,000 Chinese women [1] fell victim to this terrible fate.

A Japanese comfort house in Jiangwan Town (江湾镇) in Shanghai. Source: Beijing Youth Daily

In Shanghai, as many as 158 comfort houses [2] were believed to have existed during the war, the most among all the provinces that the Japanese controlled during wartime, stretching from Inner Mongolia to Guangdong. Housed in former bars, guesthouses, clubs, offices and confiscated villas and lilongs, the comfort houses left no distinct architectural imprint, only a lingering ‘dirty’ air for subsequent residents who moved back in after the war.

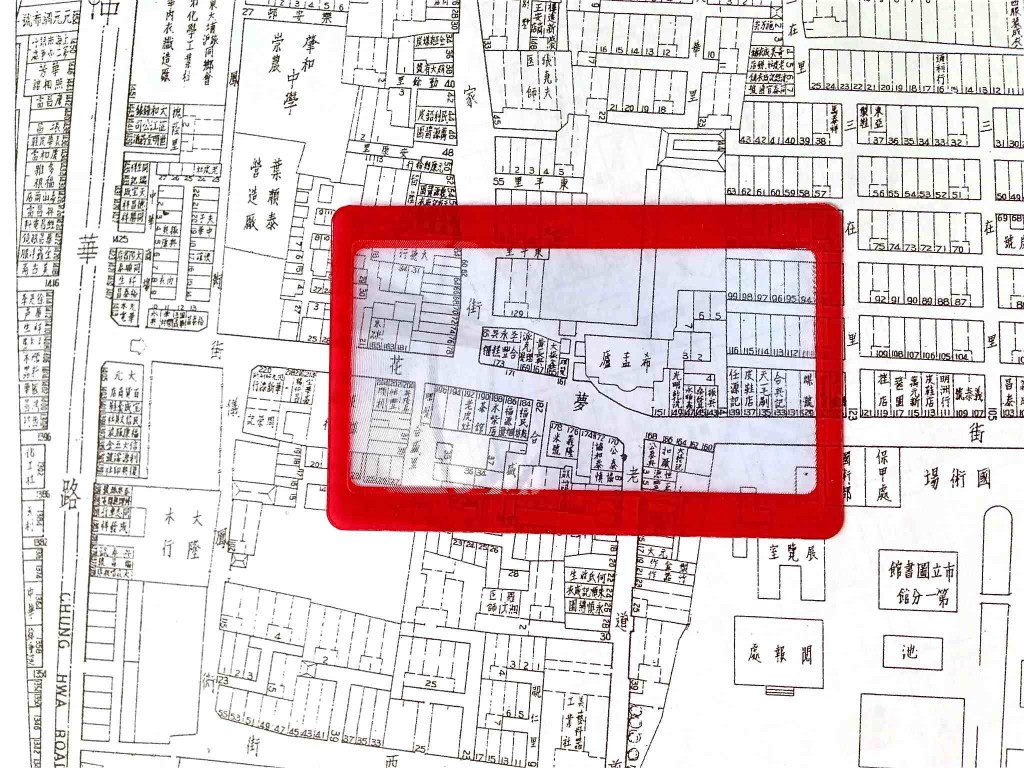

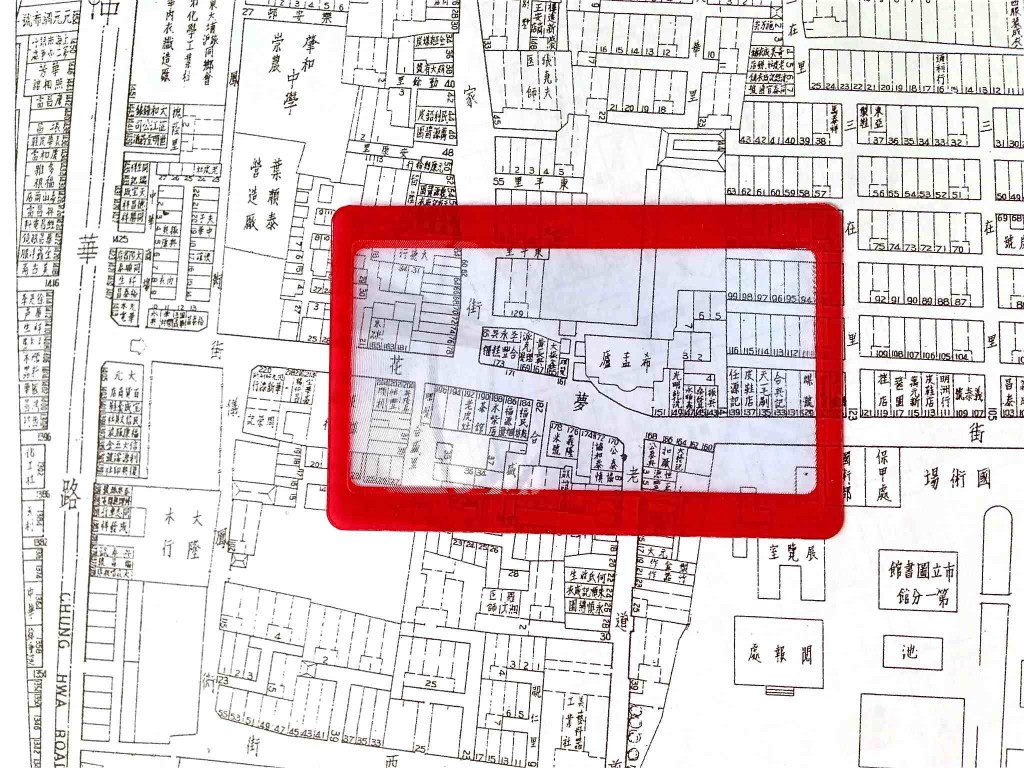

One of them is a three-story villa on Menghua Jie (梦花街) or “Dream Flower Street”, amidst a cluster of lilongs (里弄) in Shanghai’s Old Town (see color photo above). It is located near the edge of where the old city walls that were first built in 1554, ironically to ward off preying Japanese pirates. Little did the Ming dynasty residents know that centuries later, their haven would be invaded and violated within those very confines.

Map showing the villa Ximeng Lu (希孟庐) located on Menghua Jie (梦花街) or “Dream Flower Street” in Shanghai’s Old Town. Source: Old Shanghai Atlas, 上海百业指南 1946

As I was photographing, neighbors were quick to point out the villa’s sullied history as a former comfort house. A lesser known fact was that the original owner, a wealthy capitalist named Lin Guisheng (林桂生) who, in desperate hope for a son to carry on the family’s name, named his abode Ximeng Lu (希孟庐), or “Hope for an Heir”. Lin had likely chosen the character 孟 ‘meng’, meaning ‘the first child’ because it phonetically rhymed with the name of the street 梦 ‘meng’, or dream.

Lin fled to Hong Kong when the Japanese invaded Shanghai in 1937. The property was seized in 1938 and converted into a comfort house to serve Japanese military stationed in Old Town until the end of the war. Signs of struggle against the Japanese are reportedly still visible, evidenced by bullet holes in the wall surrounding the mansion.

[Read on in the next instalment, which explores Lin’s villa, and the sinister purposes it was put to during the war.]

Notes:

1. This is the most consistent as noted by according to the Chinese Comfort Women Research Center at Shanghai Normal University and Washington Coalition for Comfort Women Issues. Other Chinese sources have estimated it as high as 360,000 to 410,000.

2. Compiled by the China City Public Welfare Dissemination Alliance.

This is the first instalment in a two-part series about Shanghai’s dark legacy– buildings that housed brothels used by the Japanese Army during World War Two. This article, written by Sue Anne Tay, first appeared on her website shanghaistreetstories.com, a great resource for those who want to explore the rich history of China’s most cosmopolitan city. Also check out their Facebook page.

This is the first instalment in a two-part series about Shanghai’s dark legacy– buildings that housed brothels used by the Japanese Army during World War Two. This article, written by Sue Anne Tay, first appeared on her website shanghaistreetstories.com, a great resource for those who want to explore the rich history of China’s most cosmopolitan city. Also check out their Facebook page. Along Shanyin Lu (山阴路) in north Hongkou, one alley that originally housed Japanese families had characteristically squat house entrances with sliding wooden screens. In the now-demolished homes around Gongping Lu (公平路), I spied old kanji letterings on doors and Japanese flower motifs carved into beams. Local residents led me up to a fortified roof of an old four-storey building where keyholes were built into raised walls for Japanese canons and snipers. During the war, soldiers would have been able to see black plumes of smoke in the distance where heavy fighting took place along Suzhou Creek.

Along Shanyin Lu (山阴路) in north Hongkou, one alley that originally housed Japanese families had characteristically squat house entrances with sliding wooden screens. In the now-demolished homes around Gongping Lu (公平路), I spied old kanji letterings on doors and Japanese flower motifs carved into beams. Local residents led me up to a fortified roof of an old four-storey building where keyholes were built into raised walls for Japanese canons and snipers. During the war, soldiers would have been able to see black plumes of smoke in the distance where heavy fighting took place along Suzhou Creek.

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

Do anyone live in that villa today?