A Social and Visual History of the Dadao: China’s ‘Military Big-Saber’ (II)

- By Guest blogger

- 16 July, 2014

- 1 Comment

Author and scholar Ben Judkins describes the Dadao, or ‘big saber’, a weapon that saw use even during the war with Japan in the 1930s and 1940s. This is the first of two installments of an article first published on Judkins’ blog Kung Fu Tea.

The Dadao as a Paramilitary and Militia Weapon

Selection bias is an issue that every military historian must confront. There are a handful of photographs and historical accounts of the Dadao’s use by Republic of China (ROC) troops which have had a disproportionate impact on how we imagine the weapon in the west today. In reality most troops in the various ROC armies were not organized into “Big Sword Teams” and we are still talking about the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident” because such events are so rare. In fact, the story of this supposed triumph is really a very sad tale. If the Chinese troops had been better armed, reinforced and had more ammunition they would not have been forced to close with the Japanese and engage them with swords and bayonets in the first place. It is hard to imagine that there were really any commanders in the war hardened Chinese army of the 1930s or 1940s that actually wanted to engage the enemy with a sword charge.

Militia and paramilitary groups were in a different situation. These were basically local support troops. Their job was usually to secure rear areas and maintain order in the countryside. They were not expected to act as front-line troops. As we have already seen, the Dadao had a long and respected relationship with “law and order.” While the modern collectors like to focus on the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident,” the actual truth is that these swords were much more likely to be used in the commission of “police actions” or (war crimes, depending on one’s perspective) than anything else. For that purpose they proved quite effective.

They were also favored by militias for a number of other reasons. While Mauser rifles were cheap enough that warlord armies and criminal gangs could buy them by the crate, the same could not be said of local militia. These small groups were often comprised of struggling farmers just trying to get enough to eat and feed their families. Modern rifles and large stocks of ammunition were often not an option for militia groups.

As a result, both spears and Dadaos tended to be frequently seen in peasant groups and revolutionary societies. These weapons could be quickly produced by any local smith, and they often helped to augment the few modern rifles that were laying around the village. In this sort of landscape the Dadao was still a very effective weapon. The Dadao also had a certain cache in peasant circles as it harkened back to the “Big-Sword” militias of the 19th century and the vast body of folklore that surrounds them.

Yin Yu Zhan. Illustration from Slashing Saber Practice, 1933. Kennedy and Guo provide a detailed discussion of his publications in their volume, Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals, 2005. According to Yin Yu Zhan the ideal Dadao is 35 inches long and 3.5 pounds.

Swords were also favored by the martial arts teachers who often served as instructors of militia groups or other civilian paramilitary organizations. Most Chinese martial arts had sword forms in their repertoire and these could be simplified to fit the Dadao. Further, as a two handed chopping weapon it was not totally unfamiliar to the peasant troops who were asked to use it.

In southern China Cheung Lai Chuen, the founder of Pakmei (White Eyebrow) gained local fame by training a civilian “Big Sword Team” at the local Guoshu Institute in Guangdong during the 1930s. Of course Cheung was closely allied with the GMD. The leaders of the Foshan Hung Sing Association (formally closed by the Nationalists in 1927) returned to the area from Hong Kong in the late 1930s to train a Communist militia force.

If anything the Dadao was even more popular with martial artists in the north. In 1933 Yin Yu Zhan (an important Bagua teacher, his name is also rendered Jin En-Zhong) published a manual titled Slashing Saber Practice (Shi yong Da Dao Shu). This work is interesting because it not only discusses practical techniques for using the Dadao that may date to the late 19th century, but because the author takes the time to briefly discuss the role of the Dadao in recent Chinese military history. He notes a number of battles in the first Sino-Japanese war (1894-1895) in which this weapon was used effectively, and claims that when properly understood it still had a place on China’s modern battlefield.

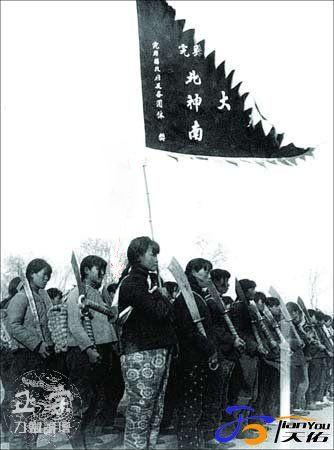

William Acevedo was kind enough to send me a copy of this picture where the banner being held in the foreground is now legible. Thanks so much! “Guangdong Province Women Teachers sends the 29th Army relief goods.” Thanks goes to my brother Sam in HK for a quick translation.

In the hands of teachers like Cheung Lai Chuen and Yin Yu Zhan the image of the Dadao was transformed once again. More specifically, it was democratized. What had once been a sign of state authority was devolved to the individual citizen who, through training and hard work, could now “defend the nation.”

For martial artists the Dadao and the bayonet became very visible symbols of the place of traditional hand combat in the modern world. They were concrete reminders that could be pointed to every time the “May 4th Reformers” began to complain about how there was no place for an activity as “backwards” and “superstitious” as boxing in modern China. Not only could the martial arts still exist, they were desperately needed by both the state and local government as they attempted to raise militias and paramilitary groups.

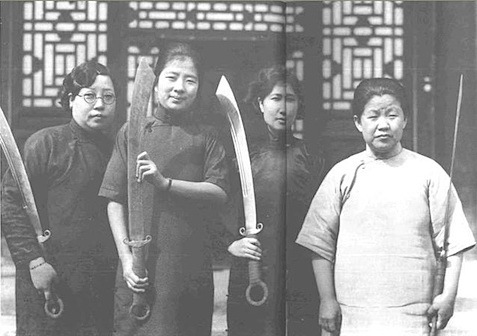

Members of an all-female militia armed with Dadaos. I am currently looking for any information about the date or origin of this photo. Please contact me if you know where the original was published.

This democratization of violence extended beyond just weaponry. During the 1920s women started to make great strides towards equality in modern Chinese life. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Jingwu Society, a national martial arts organization from Shanghai that accepted female members on equal terms. The later state sponsored Guoshu movement also promoted female martial artists, though more grudgingly.

In the 1930s all female militia groups and paramilitary auxiliaries were created. These women often received some rudimentary training and were occasionally armed with the venerable Dadao. It was not practical to arm them with rifles, and machine pistols were often too valuable. For auxiliary organizations serving in rear areas, the Dadao once again proved to be the perfect weapon.

It is also interesting to note how seriously many of these women took their training and arms. Many decades after the end of hostilities, civilian descendants of some of these original militia groups still practice with the Dadao in Taiwan. This is a fascinating artifact of the weapon’s rich association with Chinese life in the mid-20th century.

Women holding Dadaos. William Acevedo has informed me that they may have raised the money to pay for a shipment of weapons are are posing with some of the swords in the above picture prior to their donation. If anyone else has more information of this photo (or a better copy of it) I would like to hear from you.

Here are the same four women with officers from the 29th army. Note the soldier in the left side of the picture holding a Dadao at attention. Source: William Acevedo. This photo is part of the memorial at Xifengkou, ca. 1933.

Collecting Antique and Vintage Dadaos

The last section of this article addresses the Dadao as a physical object. As a general rule antique Chinese swords are difficult to collect. Authentic examples are rarely exported from China (which strictly controls the trade in antiques) and the few that are for sale in the west often sell for thousands of dollars. Many of the swords that are for sale out of China are either partial or complete fakes. While other countries may have a “cottage industry” in the production of doctored weaponry, the Chinese antique market mass produces fakes on an almost mind-boggling scale. If you go to eBay and type in “antique Chinese sword” almost everything you see from China (maybe 98%) will be a fake.

As a result, most students of Chinese martial studies and the Chinese martial arts have never actually held a genuine example of the weapons that they write about or train to use. This is a less than satisfactory situation. I strongly believe that a familiarity with actual historic weapons is a needed antidote to many of the myths that are commonly circulated in both historic and practical circles.

Dadaos are interesting in this regard as they occasionally appear on the antique market at reasonable prices. They are not antiques and can be exported from China. Hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of these weapons were made during the 20th century, making them quite a bit more common than Qing-era regulation sabers.

Fakes, often of poor quality, are still a problem. This is ironic as occasionally one can buy an authentic Dadao for less than a fake copy. If you are thinking about buying a Dadao do your research. Visit electronic forums with a community of experienced collectors and familiarize yourself with vendors who sell legitimate artifacts. And remember, everyone in the collecting world gets burned at least once.

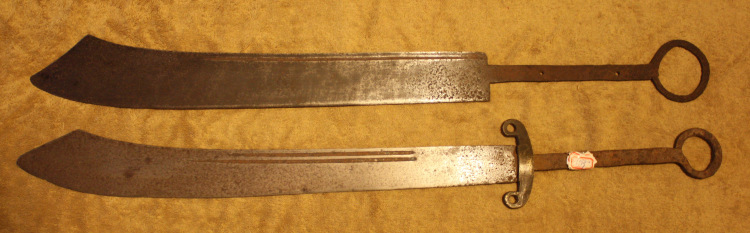

Two mid-20th century Dadaos from the author’s personal collection. Photo Credit: Tara Judkins.

Pictured above are two examples of Military Big-Sabers from my own collection. One of these swords was bought from an antique dealer in the US and the other from a trusted source in China. It is evident from the degree of corrosion on the blades that both date back to at least the mid-20th century, but it is impossible to say too much more. So many different swords were made by so many different shops that it is nearly impossible to guess at the origin of a blade from its style.

While almost identical in length this pair of swords nicely illustrates the immense variability that one sees in the military Dadao.

Top

- Total Length: 79 cm

- Blade Length: 53 cm

- Handle: 20 cm

- Blade Depth: 7 cm

- Width at Spine: 7 mm

- Weight: 1210 grams

- Point of Balance: 20 cm ahead of the base of the blade.

Bottom

- Total Length: 79 cm

- Blade Length: 56 cm

- Handle: 16 cm

- Blade Depth: 6 cm

- Width at Spine: 7 mm

- Weight: 938 grams

- Point of Balance: 14 cm ahead of the base of the blade.

Both blades are identical in length, but the similarities end there. The top Dadao is a heavy chopper. The blade has a thick spine that does not taper as it approaches the tip. The blade also has a simple straight ground v-shaped profile. As a result the weapon feels heavy in the hands and it wants to fall forward when swung. It takes two hands to wield this Dadao, which feels as much like an ax as anything else.

At one point in time the weapon probably had a simple sheet-metal guard which has since been damaged and removed. Likewise it would have been issued with a wood handle held in place with two rivets. The handle slabs have subsequently rotted away, which is common on vintage Dadaos (examples with good condition handles are rare and command a premium). When new the hilt was likely wrapped with a cotton cord to improve the grip.

The bottom sword is a much more refined weapon. While the same length it weighs less and is better balanced. The blade is longer than the preceding example, but the width of the spine tapers dramatically after the first half of the blade. This is a standard sword forging technique and it greatly improves the feel of the blade. The blade is also slightly narrower and can easily be used with a single hand. In fact, that is what any skilled swordsman would prefer to do. However, the handle is still long enough to get a second hand on it for difficult cuts.

Some modern sources go to great lengths to disparage the quality of the Dadao. The Nationalist Party did have trouble producing quality weapons, and the Communists gorillas forces were basically forced to use whatever they could get. It would appear that this general reputation for shoddy construction has worn off on the Dadao as well.

Kennedy and Guo, in an otherwise good article on the Dadao in the Republic of China Army, characterize the physical construction of the Dadao as being too short, too light and too shoddy to strike fear into the heart of an enemy (“Bridges and Big Knives.” In Classical Fighting Arts Vol. 2 No. 14. pp. 55-60). I have studied the Dadao for a number of years now and have handled dozens of examples, and I must say that I respectfully disagree with their overall assessment of this weapon.

“Chinese armies and railway men tore up their railways to prevent the Japanese from using them. Then the railway men carried away the steel rails and girders and welded them into big swords for soldiers and guerrillas to fight the enemy. This is a Chinese railway worker, member of a group of 60 railway workers who banded together to form a cooperative. They use blacksmith forges and bellows to melt and weld the steel rails, then hammer them into swords for use against the enemy.”

Late 1930s

Photographer: Agnes Smedley

Agnes Smedley Collection

Volume 38, MSS 122

While nowhere near the quality of a fine Katana, the average Dadao is very study. Most of them appear to have been made to same standard as a robust piece of farming equipment. That is not much of a surprise when you think about where most of these things were actually made or who used them.

Like any other tool, the Dadao was expected to be used in the field, day after day, and not break. If that is your measure of “quality,” then the Dadao does quite well. Especially when we remember that the Katana is a delicate weapon that requires a finely trained hand. During WWII they did fail under battle field conditions, rather frequently. While not elegant, the Dadao is clearly the more robust weapon. When supplying a peasant army that toughness counts for a lot.

It is certainly true that some non heat-treated Dadaos, cut directly from thin sheet steel, exist. Some have even ended up in museums (one of which was photographed by Kennedy and Guo). In my experience these are the exception rather than the rule. In fact, I suspect that many of these lighter weapons were actually produced for martial artists in the 1950s and 1960s when there was a general move towards more flexible, low quality blades.

The average Dadao from the 1920s-1940s had a heavy blade with a V-shaped profile that descends from a thick spine. The body of the blade is usually mono-steel, though finely laminated examples do turn up. I suspect that they are not more common only because no one bothers to polish and etch these swords.

Almost all period Dadaos that I have encountered have a high carbon steel edge inserted into the blade during the forging process and are differentially heat treated. This may seem like an unexpected luxury on such a utilitarian object, but it was actually the standard way that all knives, and even scissors, were being produced in China by the 1930s. That same very basic technology seems to have applied to the Dadao as well.

Clearly not everyone who produced Dadao’s was a trained blade-smith. I rather suspect that most of these weapons were made by blacksmiths or in local machine shops. As a result, some examples (like the one on top) lack details that you would expect to see on a sword blade. Still, for a two handed chopper what they produced was more than sufficient. If anything the top blade in the photo above is over-built. It appears to embody the same construction ethos as an armored tank. The weapon on the bottom is much more refined and it was probably made by someone who understood the art of sword construction.

Genuine Dadao’s are rarely elegant weapons. Their proportions are never perfect, and many look as though they were carved from a block of steel with a dull chisel. They came in many shapes and sizes. Some had wood handles, others were bound only in cloth. Most were issued without scabbards and were slung across the back with a length of cord. A few others had nicely constructed leather coverings. Many were issued in dull colors, but some sported eye-catching red handle wraps and flowing scarves. All of this reflects the wide assortment of regular and paramilitary forces that employed these weapons for almost half a century. This variety is one of the things that makes the Dadao such an interesting subject of study.

Modern martial artists may be more interested in the high quality reproductions of these weapons that are currently for sale. Hanwei, Cold Steel and Kris Cutlery (among others) all offer their own versions of the Dadao that no doubt surpass the originals in terms of quality control and steel strength. These blades, rather than vintage examples, should be the first choice for anyone interested in doing cutting or forms practice with a realistically weight weapon. Obviously caution, common sense and formal training are the key to doing either activity safely.

Lastly, if you are interested in learning more about historical Dadao techniques, Yin Yu Zhan’s 1933 manual has been translated and republished by a group of historical fighting enthusiasts in Singapore. You can find it here.

While only one example of the sorts of techniques that were popular in the 1930s, I think that this project serves as a model for future research. Hopefully students of other styles will investigate and revive their own 20thcentury Dadao fighting styles. This weapon still has much to teach us about the modern history of the Chinese martial arts.

Undated photograph of a Chinese soldier and his Dadao.

Conclusion: The Dadao and the Creation of Citizen Soldiers in 20th Century China

The Dadao is one of the most iconic images to emerge from China during the first half of the 20th century. It is strongly associated with the ideas of both “resistance” and “social order.” It became a favorite weapon of martial artists, elite troops and local paramilitary organizations. Far from being an anachronism, it actually seems to have embodied the spirit of the age. Artists, poets and propagandists all found meaning in this simple weapon.

That meaning was not static. It changed and evolved. Civilian martial artists played a critical role in this process. At the end of the Qing dynasty, the Dadao was a somewhat obscure infantry weapon in a rapidly modernizing army. In the hands of law enforcement officers it became an instrument of “official terror” and a reminder of where authority and legitimacy in China’s rapidly changing landscape actually resided. In this setting the Dadao represented the claims of centralized authority. As a constantly displayed reminder of the vagaries of “official justice” it was feared as much as it was respected.

These claims did not go uncontested. Warlord armies and bandit groups also made use of the Dadao. However, it was the creation of numerous paramilitary groups and militias in the 1930s and 1940s that cemented the Dadao’s relationship with the modern Chinese martial arts and its place in the public imagination.

Martial arts instructors across China found that there was once again a practical demand for their services. The Dadao could be produced locally and was easily adopted by a large number of different fighting styles. In the hands of China’s martial artists this sword was transformed from an instrument of “official terror” to a symbol of community and personal empowerment. The public image of this weapon was democratized in ways that are hard to imagine. In fact, the images that these individuals created in the 1930s and the 1940s still effect how we think about the Chinese martial arts today. While this has only been a brief introduction to the social history of the Dadao, I hope that it will inspire some of you to go out and research the subject more thoroughly.

Japanese soldiers carrying a trophy sword in Manchuria, 1932.

© Ben Judkins. No part of this article may be reproduced without the author’s prior permission.

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

British military swords were the symbol of bravery and courage of British military people. But now mostly they are owned by the antique collectors. Such swords are royal and reflect their symbol.