For Whom the Gongs Toll

- By Peter Harmsen

- 4 May, 2014

- 1 Comment

Hemingway and China. It’s not two words that are placed alongside each other very often, and for good reason. The iconic American writer had very little interest in the Middle Kingdom, and might never have visited if it wasn’t because his wife at the time, world-famous war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, was as eager as he was indifferent.

Hemingway and China. It’s not two words that are placed alongside each other very often, and for good reason. The iconic American writer had very little interest in the Middle Kingdom, and might never have visited if it wasn’t because his wife at the time, world-famous war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, was as eager as he was indifferent.

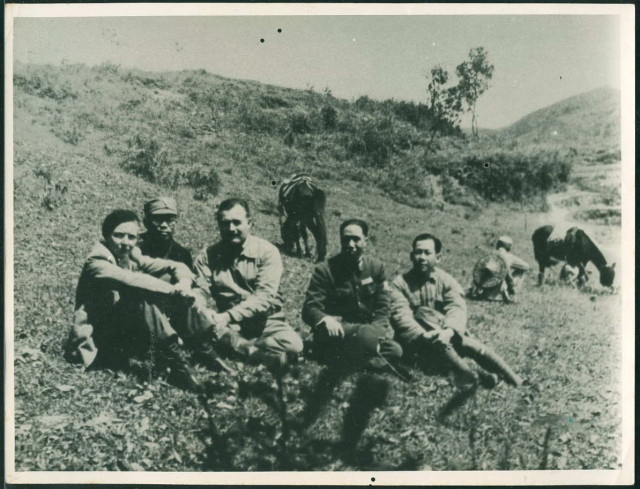

The photo above shows Hemingway in China’s wartime capital in early 1941, seated between Gellhorn and Song Meiling, better known abroad as Mme Chiang Kai-shek. Although it’s not obvious from the photo, the meeting didn’t go well. Gellhorn explains why in her memoirs Travels With Myself and Another, which remain the primary source of the couple’s entire East Asian sojourn.

Hemingway hit it off with Mme Chiang, but then Gellhorn raised the issue of lepers roaming the streets of China, forced to beg for a living. The Chinese First Lady exploded in anger. The Chinese were humane, she said, and unlike westerners they would never lock lepers up in isolation from other people. “China,” Mme Chiang said in conclusion, “had a great culture when your ancestors were living in trees and painting themselves blue.”

Gellhorn and Hemingway in China. The slightly dissatisfied expressions on their faces may not be accidental

What ancestors, Gellhorn thought to herself, apes or ancient Britons? The encounter wound up with a somewhat strained attempt to part on amicable terms. Mme Chiang offered a peasant’s straw hat and a jade brooch to the famous couple. Gellhorn liked the hat but thought the brooch was “tacky” and was not appeased. Hemingway was amused. “I guess that’ll teach you to take on the Empress of China,” he told his wife with a laugh tainted by Schadenfreude.

The truth was Hemingway didn’t like China. He wasn’t impressed by the culture before he left the United States by ship in February 1941, he arrived determined not to be impressed, and he left duly unimpressed. In her memoirs, Gellhorn refers to him consistently as Unwilling Companion, or U.C. for short.

Gellhorn, who was sent to China by her employer Collier’s to report on the war with Japan, had dreamed since childhood about going to the Orient. Hemingway, who wrote dispatches for the newspaper PM, had not spent his formative years “stuffing his imagination with Fu Manchu and Somerset Maugham,” but he went along, probably out of loyalty to his wife.

After making the dangerous journey from Hong Kong to unoccupied southwestern China, Gellhorn soon lost all illusions she might have had about fighting China. Not only was she turned off by the lack of any signs that the war against Japan was still being waged with any discernible vigor. She also felt disgusted at the medieval squalor, the corruption and the deep social divisions.

“An overlord class and tens of millions of expendable slaves was how China looked to me,” Gellhorn wrote decades later in her memoirs. Hemingway was no big comfort, displaying an attitude of “I told you so.”

“An overlord class and tens of millions of expendable slaves was how China looked to me,” Gellhorn wrote decades later in her memoirs. Hemingway was no big comfort, displaying an attitude of “I told you so.”

For Hemingway himself, one of the highlights of the trip was a “booze battle” – the famous American drinker against 14 Chinese officers taking turns doing bottoms up. “Slowly officers grew scarlet in the face and slid beneath the table; others went green-white and fell as if shot,” Gellhorn reminisced. Hemingway, by contrast, “was planted on his feet like Atlas.”

Another highlight was a secret meeting with Communist leader Zhou Enlai, whom the couple was taken to see blindfolded. Zhou worked his famous charm on the two Americans, and they immediately saw him as a winner. Gellhorn even had a crush on Zhou worthy of a teenage girl: “I was so captivated by this entrancing man that if he said, take my hand and I will lead you to the pleasure dome of Xanadu, I would have made sure that Xanadu wasn’t in China, asked for a minute to pick up my toothbrush, and been ready to leave.”

Source: Martha Gellhorn, Travels With Myself and Another. New York: Penguin, 2001.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

[…] Harmsen of the excellent China in WW2 blog has a great write-up of Ernest Hemingway and his then-wife, war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, traveling to Chongqing […]