Surrender in Nanking

- By Guest blogger

- 23 September, 2015

- 3 Comments

The dominant narrative of Japan’s surrender is well-known: from Potsdam to Hiroshima, Soviet advances, Nagasaki and the official surrender ceremony on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. This narrative of Allied power and Japanese capitulation stands in contrast to the experience of surrender and reconstruction throughout Asia. The Japanese army in China, known as the China Expeditionary Army (CEA), provides one such counter narrative. Much of the CEA remained in China for the better part of a year after surrender. Most of it was fully armed and frequently still in charge of rail zones, cities, and even many towns in northern China.

Nanking was China’s capitol from 1927–1937, when it was occupied by Japan, and again from 1945–1949, when it was toppled by Mao Tse-tung. Between 1937 and 1945, Nanking was the seat of the wartime collaborationist regimes, which were disbanded on 16 August. In a second radio broadcast on 15 August, this one by Chiang Kai-shek, who made it clear that he wanted to pursue a benevolent policy vis à vis the Japanese: the Kuomintang would return ‘virtue for malice’.

The CEA learned of the decision to surrender late in the evening of 15 August. Its Commander-in-Chief, General Okamura Yasuji, who commanded more than a million undefeated soldiers, opposed the decision. Nevertheless, the Emperor had ordered him to surrender and surrender he did. On 20 August, the CEA ordered all units to cooperate with the KMT in China’s post-war reconstruction. At the same time, stern action was to be taken against any and all anti-Japanese actions by the communists.

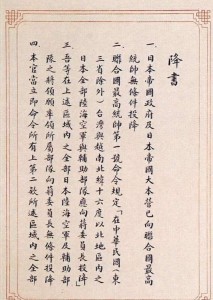

After the inevitable negotiations, General He Yingqin, representing China, flew into Nanking on 8 September. The surrender ceremony took place at 9 o’clock (local time) the next day (the ninth hour of the ninth day of the ninth month), presumably according to Chinese wishes, in the auditorium of the Central Military Academy in Nanking. It has been reported that the Chinese wanted to use a round table and avoid humiliating the vanquished Japanese, but this idea was vetoed by the Americans. Okamura presented the Japanese Instrument of Surrender to He and thus brought Japan’s disastrous eight-year invasion and occupation of China to an official end.

After the inevitable negotiations, General He Yingqin, representing China, flew into Nanking on 8 September. The surrender ceremony took place at 9 o’clock (local time) the next day (the ninth hour of the ninth day of the ninth month), presumably according to Chinese wishes, in the auditorium of the Central Military Academy in Nanking. It has been reported that the Chinese wanted to use a round table and avoid humiliating the vanquished Japanese, but this idea was vetoed by the Americans. Okamura presented the Japanese Instrument of Surrender to He and thus brought Japan’s disastrous eight-year invasion and occupation of China to an official end.

The ceremony was a solemn affair between men who knew one another. At least some of the Chinese victors respected and admired Japanese military figures such as Okamura; General He is said to have apologised to ‘sensei’ Okamura for subjecting him to the indignity of having to surrender. (In the post-war era, He travelled to Japan every year to celebrate Okamura’s birthday). This can be explained in part by old school ties: the major military academies in pre-1945 Asia were Japanese, and many on both sides of the conflict were products of these institutions. Chiang himself had studied at a Japanese military preparatory school. He was a 1916 graduate of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy, Okamura a 1904 graduate. Okamura had for some years been entrusted with the supervision of Chinese students at the Academy, and was clearly remembered with a great deal of gratitude.

The war ended suddenly, without the Japanese in China being defeated. Events took the KMT by surprise. The KMT military forces had borne the brunt of the fighting, suffering horrendous losses, and had been pushed far into the interior of China. Chiang needed time to move back into China’s large urban centres. The Japanese were ordered to surrender only to the KMT and to remain in control until handovers were physically possible. Even after formal surrender, the CEA was asked to retain responsibility for maintaining public order in places such as Nanking, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. The CEA was ordered to defend its positions, and did so, fighting against communist guerrillas and even retaking territory from the CCP (Chinese Communist Party).

Especially in northern China, the Japanese were in control of territories contested by the KMT, the communists, and even foreign military forces. In Shanxi in particular, the old warlord Yan Xishan (who graduated from the Japanese Imperial Military Academy in 1909) actively recruited the local Japanese soldiers to fight against the communists. Although he described this recruitment as ‘retained technicians on individual and voluntary basis,’ most analysts interpret his actions as violations of the Potsdam Declaration and General Order No. 1. Nonetheless, Japanese soldiers were still fighting in Shanxi in 1949.

To the astonishment of Western observers, armed Japanese soldiers were still patrolling Chinese cities. It is said that in post-surrender Shanghai, ‘American servicemen respectfully stepped off the sidewalks to make way for armed Japanese patrols.’ The first journalists to enter Nanking were puzzled: ‘there is nothing in Nanking that indicates its liberation … Okamura is still enthroned in the Foreign Ministry Building, Japanese gendarmes still occupy the former premises of the Judicial Yuan. Japanese sentries are posted everywhere, with orders to maintain the peace and protect their compatriots.’ Indeed, Chiang retained Okamura as a military adviser even during his 1948–49 war crimes trial, at which he was convicted, then pardoned and returned to Japan.

To the astonishment of Western observers, armed Japanese soldiers were still patrolling Chinese cities. It is said that in post-surrender Shanghai, ‘American servicemen respectfully stepped off the sidewalks to make way for armed Japanese patrols.’ The first journalists to enter Nanking were puzzled: ‘there is nothing in Nanking that indicates its liberation … Okamura is still enthroned in the Foreign Ministry Building, Japanese gendarmes still occupy the former premises of the Judicial Yuan. Japanese sentries are posted everywhere, with orders to maintain the peace and protect their compatriots.’ Indeed, Chiang retained Okamura as a military adviser even during his 1948–49 war crimes trial, at which he was convicted, then pardoned and returned to Japan.

Perhaps because Chiang needed the Japanese, surrender was not followed by the ruthless brutality seen in Soviet-occupied Manchuria. Indeed, given the many complications that existed, it is surprising how smoothly the handover went. Both victors and vanquished behaved very well indeed.

David Askew is Associate Professor of Law, Asia Pacific University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

Hello,

Very interesting article indeed.

Thank you very much for posting it on line.

As a keen WW2 enthusiast, it is always welcome to read material on this subject.

Rgrds,

Neil

Very glad to hear that. Any topics in particular you would like to read more about, please don’t hesitate to send a message!

Great article, very interesting and fascinating period of Asian history.